Jenna Bliss’s True Entertainment (2023) feels like a haphazardly made mockumentary, allegedly depicting a time leading up to the 2008 economic crisis and the U.S. presidential election. Given widespread speculation about an impending recession and the recent election, I expected the video to resonate in some way. I pretty much never see an exhibition twice on my own accord, but I went out of my way to see Bliss’s video at Amant not once, not twice, but three times.

It was stupid the first time I watched it, but I was curious if something major went over my head. So for the second watch, I took a friend, who only confirmed that it’s stupid. While it’s obvious that it’s intentionally absurd, I don’t think Bliss meant for this to come off as stupid. I went back a third time with the idea that I’m challenging myself to try to write a positive review about the video. I couldn’t bring myself to write a disingenuous positive review, so here’s my extremely belated but honest review.

The premise of the video is a gallery’s owners and staff preparing an Art Basel booth to showcase the edgy works of one painter, a former model whose glamorous reputation has expired. Some cliché dynamics with predictable tensions are laid out:

A pretty, rich girl gallery assistant and a disgruntled, average-joe art handler in a casual sexual relationship

Clout-hungry gallery owners who need the show to succeed at all costs to solidify their status as the cultural elite, alongside visitors who are pseudo-intellectual grad students without the capital to get their pretentiousness taken seriously

The artist who is paranoid about being a joke and the art market leading up to the 2008 economic crisis (wink wink at Russian oligarchs looking for money-laundering services?)

At best, this video was a bizarre yet humorless inside joke for the art world. Contemporary art has a bad habit of equating the act of pointing at problems with critically engaging with them. It makes sense if the problem is novel, but the “art world people are exclusive and weird” trope is so overdone, and I couldn’t see what was clever or special about Bliss’s representation of it.

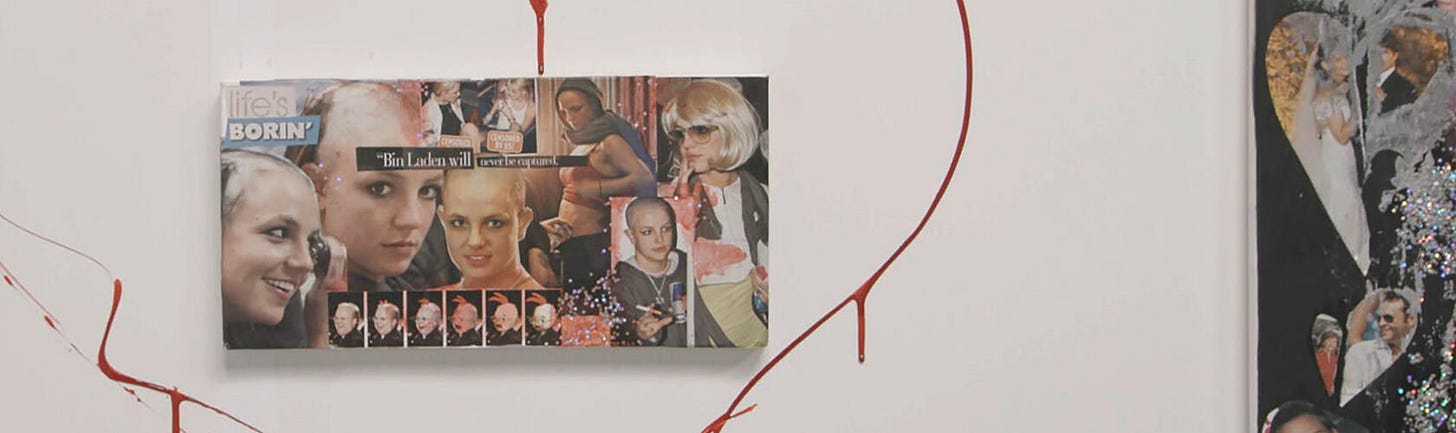

The most memorable part of the video is when the gallerist, “Florian,” emphasizes to the assistant that she has to stress that the artist, Lola Van Haas, was an “it” girl, which is an important selling point since her collages of celebrities are cringey and don’t have much visible artistic value. Is this fictional artist perhaps a caricature of Jenna Bliss herself? Is she projecting paranoia that maybe her own art is mediocre, but she’s been getting shows in the U.S. and Europe because of the social circles she landed herself in? I wouldn’t condemn her for playing the game whose rules are set within the framework of neoclassical economics.

This actually lands itself pretty well considering that people talk about MFAs similarly to MBAs. You don’t get the degree to refine your skill. You get it in hopes that going through the program will embellish you with a network that will place you in proximity to power and boost your journey toward visible success. Doesn’t this align perfectly with the principles reinforced by an era of LinkedIn, where young people are told that it’s all about who they know? At the very least, the video helped me understand why much of contemporary art feels so hollow today. People are skipping steps. They are jumping right to getting others to know about them (exposure) before they get to know themselves and refine their practice (development).

My first time watching, I did wonder how Bliss scored a show at Amant, a relatively new but seemingly serious institution of contemporary art. Knowing that Amant is built on billionaire money, it was a surreal experience watching the class-conscious scenes in this video that lightly touch on criticism of, yet the desire to be a part of, the extremely wealthy class. It’s hard to take True Entertainment’s class-conscious critique seriously when it’s being shown at Amant, an institution built on billionaire wealth—a glaring reminder that even art that claims to resist the system often finds itself funded by it.

Even after my third visit, I couldn’t decipher how showing this video at Amant could be justified. I hoped that Bliss was trying to tell viewers that she’s against this money-glorifying art fair industrial complex, but how could I be convinced of it when I can’t disconnect her message from the reality that Amant’s founder, Lonti Ebers, is the spouse of the CEO of Brookfield Asset Management, which has fueled gentrification by transforming affordable housing into high-end developments, displacing long-term residents and eroding historically diverse communities?

I’m not trying to antagonize Bliss. Really, I am just spiteful of the dilemma: we all see that the system is fucked up, but we still prostitute our art and labor to the wealthy whenever we are given the chance. And that’s why I’m mad at True Entertainment. It’s not resisting or even risking anything. Just plainly depicting a system of oppression as another form of entertainment.

Jenna Bliss

September 19, 2024 – February 16, 2025